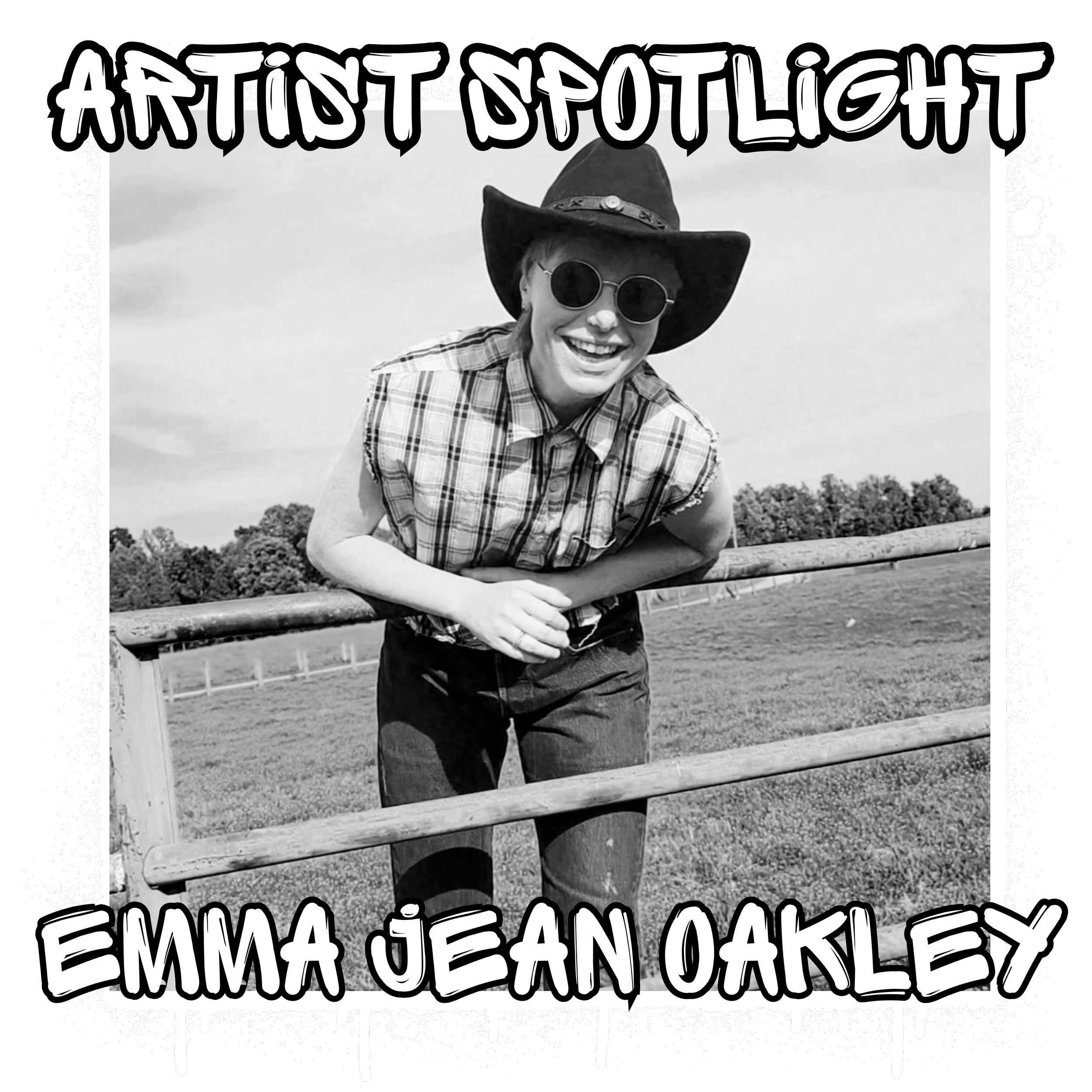

Born Into Music, Raised on Heartbreak, Becoming Herself in the South

Emma Jean Oakley’s story begins before she remembers anything at all. Before the friendships that shaped her, before the heartbreaks, before the voice memos full of quiet ideas, before she ever understood what a song could do. It begins with Shania Twain. “My mom introduced me to Shania Twain before I left the womb,” she says, and the affection in her voice makes it clear how deeply those early sounds rooted themselves. She grew up on K95, her local country station, where Shania and the women of nineties country filled her world with the first hints of who she might become.

By age four she was in New York City on her stepdad’s shoulders, watching Shania perform on the Today Show in 2003. It was her first concert, the first moment where music stepped out of a radio and into the air. “Here is a [video of] me on my step dad’s shoulders watching the show,” she says, referring to a YouTube video. She did not think about the stage or the production or the artistry. She remembers only this: she “was just having the time of my life.”

Music did not enter her life halfway through childhood. It grew up with her. It held her. “My parents and friends definitely influenced my music the most,” she says. “I definitely still associate a lot of nineties country music with them.” As she got older, new sounds entered the picture. “We listened to a lot more rock music as I got older, things like Foo Fighters, Green Day, etc.” Her stepdad introduced her to Paramore in sixth grade. Friends shared Boys Like Girls and The 1975. These artists did more than shape her taste. They shaped her instincts. “Absolutely… ultimately they did teach me how to write memorable melodies.”

Shania stayed central. When asked if she still goes back to Come On Over, she answers without hesitation. “100 percent, I love her.”

The First Songs, The First Sparks

Emma has been writing almost as long as she has been listening. “I have been writing nonsensical things for as long as I can remember,” she says. Her first full song arrived in sixth grade and was about “a friendship that was strenuous.” She laughs about it now, but the moment mattered. It showed her what it felt like to finish something emotional, something private, something that belonged entirely to her.

She can pinpoint the moment songwriting became part of her identity. “The moment that I started a band. I have loved it ever since.” Her mom was the first to encourage her. Others followed. Their belief mattered.

Her creative process today is quick and instinctive. “Nine times out of ten I will have a melody and lyric idea at the same time,” she says. When inspiration hits and she is not near a guitar, she reaches for her phone. “I will voice memo it immediately.” She rarely throws away early drafts. “I probably keep ninety percent of my first ideas.” She knows when a song is finished. “When you know you know.”

Some lyrics still make her pause. One line in particular unsettles her every since she wrote it. “Think you are fucked in the head.” She explains it honestly. “It is a really brutal thing to say about a person. I still care for the person I wrote it about.” She kept it because it was true in the moment. “Songwriting is a part of my processing, and this is not how I feel about the person or situation after processing further.”

Her writing protects the truth of the moment first. Understanding comes later.

Emma describes herself without hesitation. “I am a big time lover boy,” she says. Much of that softness traces back to the way she watched her parents love each other. “My dad, albeit not very good at it, loved my mom relentlessly.” She adds, “He may disagree, but I think he has pined for her since their divorce.” Those patterns of quiet devotion shaped the way she understood longing, attachment, and romantic gravity. Her song “July” helped her examine those patterns more clearly. “Owning the parts of me that I dislike have helped me accept and reframe them.”

July, Yearning, and the Songs that Made Her

Other songs began from playful ideas. “Ways To Waste My Time started as simply a lyrical exercise,” she says. She was writing lists and turning them into melodies, and the emotion came through on its own. “I would call it yearning, emotional dissatisfaction.”

Yearning is an undercurrent in her life and in her writing. It moves through her songs like something instinctive.

She names her influences with no hesitation. “If you are familiar with The 1975 you can hear them plainly in Ways To Waste My Time and Keep Me.” She does not hide what she borrows or what she reshapes. “I like to steal their riffs and repurpose them in places that feel completely fresh and new.” Their lyricism affects her as well. “I am also very lyrically inspired by Matty. He is bold and writes in metaphors a lot.”

Her taste stretches across genres. “I am a proud fan of everything from Boys Like Girls to one hundred Gecs to Lucinda Williams and beyond.”

Seven Days in Massachusetts That Changed Everything

Recording in Massachusetts with producer Tom LeBeau marked a turning point. “Tom [LeBeau] is probably the most talented musician I have ever worked with,” she says. They made the entire Throw Me a Bone project in seven days, fitting sessions between his shifts at the local music store. The pace was intense, but the environment pushed her forward. “He is so kind and hard working. It sparked a fire in me to put more diligent practice into my musicianship.”

The collaboration helped her find a sound she had been reaching for. “He definitely helped me hone in on the sound I was aiming for.” She is careful, though, not to pin herself down. “I do not know if my identity as a musician will ever be solidified. I think I am constantly evolving as I learn more and am introduced to new things.”

That time in Massachusetts did not just capture her voice. It captured her growth.

Her Queer Story, Told Softly but with Strength

Emma’s coming out did not happen in a single conversation or moment. “Truthfully, this realization did not happen in one particular moment,” she says. It built slowly over years. “It took years and years of feeling attraction and not being able to name it or being in denial of it.” Her early twenties brought clarity. “It took all of my early twenties to feel confident enough in my attraction to women to be able to claim that as a part of my identity.” She describes the shift as “a slow welling up, until I could not hold it back anymore.”

Living in the South again means coming out often. “If I have come out once, I have come out a hundred times. Especially now that I live in the South again.” She tries to speak freely and normally about her life. “I try to just pretend I do not have to come out and it is just totally normal for me to say my girlfriend.”

She has thought about responsibility and visibility. “I have no desire to be a martyr. I do not want to come across as a spokesperson for lesbianism. I just want to exist without persecution or fear.” Her art reflects her identity naturally. “The pronouns and imagery I use in the context of my artist project will inherently be lesbian, because that is what I am. I sing about what I am and what I know.”

One of the most meaningful moments came when she returned to her childhood farm to film visuals for her EP. “It felt like coming home,” she says. That place once made her feel unsafe. “That farm had been a place I felt unsafe to be an out queer person as I was growing up but now things have changed and there is a supportive community there for me.”

Richmond and the Places That Shape Her

“Richmond raised me and no other city has been able to hold me like it does,” she says. She left, and she returned, something common among people from Richmond. “Yes, I carry Richmond with me everywhere.”

Her creativity shifts with her surroundings. “I feel most lyrically inspired when I am on the road and more musically inspired when I am at home with my laptop and my instruments.”

One place feels especially grounding to her. “I frequent that bar and I just did my release show there,” she says of Fuzzy Cactus.

The Work Behind the Art

Emma is most proud of her consistency. “I am very proud of myself for the consistency and discipline I have put into this project.” She built everything from almost nothing. “I have done everything related to this project on a negative dollar budget.” That shaped the way she sees the world. “It has changed the way I see myself and the way I see the world.”

If she signs with a label one day, she knows what she needs. “I think I would need a lot of autonomy. I have a vision and I do not want it to be compromised.”

Her plans are clear. “I am hoping to be touring mid sized clubs a reasonable amount that allows me to have a relatively normal life outside of my work.” Her definition of success is simple. “Making over one hundred thousand per year from music. Enough that I can live comfortably.”

The Truth She Stands On

As our conversation softens toward its end, I shift into a quick lightning round. The lyric that feels closest to her diary is “I know that I am my fathers child.” The music that steadied her is “Anything by The 1975.” When she wants comfort listening, she reaches for “Boys Like Girls.” A moment that still feels bright to her is “My buddy Rick nailing the solo in Ways To Waste My Time at the release show.” A book that changed her is “Zami: A New Spelling Of My Name by Audre Lorde.” The artist she dreams of collaborating with is “S. G. Goodman.” Her proudest habit is “Posting my dang songs online every single day.” Her worst is “Leaving my laundry in the wash.” The advice she would give her younger self is “Time Takes Time.”

These answers reveal her in the simplest and clearest way. They show what she loves, what she returns to, what she leans on, and what she carries. When I ask what she hopes people feel when they hear her music, she gives a response that feels warm and sincere.

“When people hear my songs, I want them to hoot and or holler.”

Because at her core, Emma Jean Oakley is still the child lifted high in a crowded plaza in New York, watching Shania Twain sing into the morning air. She is still the girl raised on country radio. She is still the teenager who discovered Paramore at the exact right time. She is still the young woman writing her way through heartbreak. She is still the queer artist reclaiming a farm that once made her shrink.

She is still growing.

She is still evolving.

She is still writing her life as she lives it, one voice memo at a time.